Last summer, as I was re-reading Carl Bielefeldt’s Dogen’s Manuals of Zen Meditation, I received a very kind email from a reader asking me to offer my take on how to do zazen. I have no idea how many times I’ve offered zazen instruction in person, but in reading that request, I realized that I had never tried to write it all down. Furthermore, it had never really occurred to me that I have a particular take on it — when I explain it to someone else, I’m very aware of both Dogen’s instructions and things I’ve heard from my teachers. But the timing — that book, with this request — inspired me to look more closely at how I approach zazen, how I hear the explanation in my head.

Last summer, as I was re-reading Carl Bielefeldt’s Dogen’s Manuals of Zen Meditation, I received a very kind email from a reader asking me to offer my take on how to do zazen. I have no idea how many times I’ve offered zazen instruction in person, but in reading that request, I realized that I had never tried to write it all down. Furthermore, it had never really occurred to me that I have a particular take on it — when I explain it to someone else, I’m very aware of both Dogen’s instructions and things I’ve heard from my teachers. But the timing — that book, with this request — inspired me to look more closely at how I approach zazen, how I hear the explanation in my head.

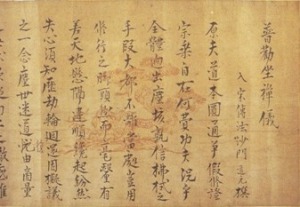

Much of Bielefeldt’s book (which I cannot recommend highly enough) chronicles the evolution of Dogen’s “Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen [Fukanzazengi]” from an earlier draft to a later one, showing that Dogen’s understanding of zazen — both how to practice it, and how to express that practice to others — was evolving. Dogen passed away when he was 53; if he’d lived to 80, I have no doubt that the zazen instructions we read in temples every evening would be different, somehow, from what they are.

I am fond of complaining that we rely too heavily on Dogen in this tradition. That doesn’t come from any complaint about him or his writings — not at all. But it seems to me that in the 800 years since his death, we should have a few more people to reference. More teachers should have stepped forward with their own understanding of the tradition. Or perhaps the institutions around this practice should have given greater voice to those who were trying, in vain, to be heard. In any case, 800 years later, it’s still pretty much all Dogen.

So on planes and in line at the bank, I have found myself picking away at my own instructions for zazen. Of this, I’m sure: if I had tried to write these instructions 10 years ago, they would have been very, very different. And I sincerely hope that 10 years from now, these instructions will be equally different, that they will have evolved with my understanding of the practice. If all goes well, I’ll read these instructions when I’m an old man and wince a little, seeing more clearly then what I don’t see clearly now.

But today, at age 40, I think this is my best effort. I put out these instructions (some are pretty standard, but a few are not) not to rewrite anything, but to put myself on the spot, to make myself open to whatever discussion or comments might follow. This is a work in progress. More than that, I do it in the hopes that it might start a dialogue, and that others might feel a push to publish their own instructions. I would very much like to read them.

_________________

INSTRUCTIONS FOR ZAZEN

Choose this place.

Whenever you can, sit with others. When you can’t, sit with others. Let others sit with you.

Wear the kashaya. Just as Buddhas sit in zazen while zazen is the activity of Buddhas, Buddhas wear the kashaya — the kashaya manifests the shape of a Buddha. Even if there is no robe, just wear it.

Do not put yourself into sitting — come empty handed. Do not make zazen — let sitting reveal itself. Do not use zazen for this or that — sitting is neither means nor end.

Spread a blanket or mat and place a zafu on top. Sit down, marking the center of the zafu with the base of the spine.

To sit in the full lotus, place the right foot over the left thigh, then the left foot over the right thigh. Rest your left hand on your right hand, palm up — the middle joint of the middle finger below aligns with the middle joint of the middle finger above, and thumbtips touch as if trying not to, just near enough to feel the electricity between them. This is called Sitting in Practice.

Reverse the legs; reverse the hands. This is called Sitting in Verification.

Sit in practice today and in two days. Sit in verification tomorrow and yesterday.

If not full lotus, half lotus. If not half lotus, rest the foot of the raised leg across the calf of the lower leg. Or kneel. Or sit on a chair. Remember that this body is the buddha’s body. Do not harm it. Also, do not underestimate it.

Always place the knees below the hips, the pelvis tilted forward, the lower back slightly curved. Establish a posture that need not fight gravity.

Be the tree beneath which other buddhas sit.

Press the hands below the navel; let them move with the breath. In full lotus, rest them on top of the heels. In any other posture, support the hands with a blanket or cushion.

Once seated, rotate the torso at the hips in wide circles, then in small ones until the spine is holding the earth in place; pull in the chin and stretch the back of the neck upwards, lifting the sky.

Take seven long breaths. As you inhale, fill the body with a wind that loops through your feet and across your thumbs. As you exhale, do so slowly, continuing until your breath has touched the far corners of the world. Exhale until nothing remains.

On the eighth breath, just breathe.

How long must one sit? How many breaths? Ancient buddhas did not measure zazen in minutes or hours.

Let in all sounds — hear the shifting of the continents, a bird turning in flight. Facing the wall, see beyond the horizon. Feel your heart beating, your lungs moving, your skin expanding and shrinking, the magnetic draw of your thumbs. Breathe in the stench and the perfume of the world. Let your tongue rest flat in your mouth, and taste.

Mara visits during zazen, but not as visions — visions, if only glanced at, will pass by like shadows. Nor will Mara come disguised as desire — desires, confronted directly, lose their power to haunt. Mara will visit as a weight on the eyelids, bearing the soft seduction of sleep. Open your eyes; if they grow heavy or the world blurs, open them wider. Keep the room cool. Let light in. Explore the waking world, not dreams.

Be the force of gravity, pulling you deep into the ground; be the weight of a flame. Do not move from this posture. With every cell in your body, every drop of blood, every inch of skin, constantly do not move.

Zazen is not non-doing; it is not non-thinking. Zazen is a deep, dreamless sleep on fire. It is clutching a boulder to your belly at the bottom of the cool ocean. Roots penetrate and plunge downward into the rough textures of the earth. A cloud dissolves into open sky.

_________________

Sitting in Practice: gōmaza (降魔坐)

Sitting in Verification: kichijōza (吉祥坐)

The phrase “weight of a flame” is taken from a verse provided by Dai-en Bennage, abbess of Mt. Equity Zendo: “Abandoning myself to breathing out, and letting breathing in naturally fill me. All that is left is this empty zafu under the vast sky, the weight of a flame.” (original source unknown)

___

Update January 20, 2019: My gratitude to Saiho Sandra Laureano, of Centro Budista Soto Zen in Puerto Rico, who very generously translated these instructions into Spanish.

🙂

Yes! Now I see certain deficiencies in my many attempts to give instructions on zazen.

I am bowled over, roll back up . Nine Bows. Lovely.

Koun, I have one question for you. You write, “Do not move from this posture. With every cell in your body, every drop of blood, every inch of skin, constantly do not move.” I also tell students not to move, but at the same time, to not be rigid like iron. A fellow named Will Johnson has a pretty good book out there called “The Posture of Meditation” in which he speaks of how posture subtly and naturally changes and flows during sitting: as we sink into the Zafu, the body settles by the force of weight, the chest moves in and out, the head subtly rests on the next in different ways. All is fine so long as comfortable and balanced, and what is comfortable and balanced may actually change and subtly adjust during a sitting. In other words, we are always subtly moving in small ways while sitting, and that is fine if we simply feel balanced. So, I tell students to sit still, but not rigidly … and also to sit in a Stillness that holds both stillness and motion.

I don’t think I am expressing this well this morning at all, but wonder if you would clarify “do not move” a bit.

Gassho, Jundo

Jundo–

Thank you. I think it’s perfectly appropriate to shift during zazen — I do. We shouldn’t lock ourselves into the posture we find when the bell rings if it isn’t the right one. And besides, as Will Johnson is saying, our bodies settle with time. (And we move even if we don’t know we do it — fast-forwarding through video of zazen shows a person very much in motion).

What I was trying to express, unskillfully, is that sitting is active. We don’t just find a comfy way of sitting and stay there — we exert ourselves in the act of sitting right where we are, even if it looks to the observer like nothing is happening. It’s not strain, just commitment to this action. Hopefully we can keep that mind even during those subtle shifts.

That said, sometimes I probably move too much. 🙂

Gassho,

-koun

Just great. Thanks for writing and sharing this Koun.

Koun, a very poetic and thorough description of sitting. But I do have a couple concerns with it. The first has to do with its very poetic nature: it may contain too many stimulants for the imagination and food for the expectation of creating an ideal state instead of being present to what is. Rather than instructing to ‘hear the shifting of the continents, a bird turning in flight’, and ‘see beyond the horizon’, why not just invite presence to the immediate miracles of a fridge turning on and off, traffic going by, the crack in the wall in front of you, etc?

Also there is the (literal) demonization of sleepiness which can add a layer of guilt and resistance. To paraphrase a talk by Joko Beck, ‘Sleepiness isn’t a sin. The body has its wisdom. If you’re really tired, the worst that can happen is you fall asleep and wake up more alert.’ Of course if it happens all the time there may be avoidance going on, or simply an opportunity to look at one’s lifestyle that is producing so much tiredness.

My final point has already been addressed: the instruction not to move. It seems to me that zazen is about optimizing motion (the body’s natural activities like breathing, heartbeat and blood flow, peristalsis, coming into and out of balance with gravity etc) while minimizing movement (conscious readjustment in response to restlessness and discomfort). I appreciate your comment about not locking into a posture but it rather being active.

Thanks for taking the time to do this.

Bud

Bud–

I agree with you about the poetic nature of it — it will speak to some, but not to others. I don’t talk like this when I guide someone through zazen in person — I’m more likely to use the kinds of examples you mentioned. These instructions shouldn’t replace a teacher; in a best-case scenario, perhaps these instructions just offer a different angle. That said, I think we shouldn’t shy away from trying to describe practice in poetic terms. I would like to keep trying, anyway, in large part because beyond the technical specifications of zazen, I have a feeling about it that I would like to share.

It wasn’t my intention to demonize sleepiness itself, just to say that we should never let sleep overcome zazen. It becomes a habit — I know. Once your body figures out that it can sit up straight in the lotus posture and just sleep, it will gravitate towards that dream space. I don’t think that a chronically sleep-deprived person should never do zazen, but as a basic rule, if you’re on the cushion and can recognize that you just can’t stop that descent into sleep, I say it’s better to get up and move around. Don’t let sleep be part of the zazen menu.

Thank you for bringing these issues up. As I wrote, I’ll keep trying to make this better.

Gassho,

-koun

thank you for this excellent and thought provoking work. one(!) question: I’m not familiar with the expressions “sitting in practice” and “sitting in verification”, beyond the postural differences you describe. can you talk about the significances and differences between these two “sittings” otherwise?

gassho,

Robert

Robert,

Thank you. I’ll try.

“Sitting in Practice” and “Sitting in Verification” are not perfect translations of kichijoza and gomaza; I chose them because they point to how we understand those terms functionally. Sitting in Practice is sitting the way that Dogen describes — it’s the gold standard. But you may notice that almost all statues of Buddha in a meditation posture show the exact opposite: legs reversed, right hand over left. This is Sitting in Verification, and the idea has been that sitting in that way is reserved only for fully enlightened beings — it’s the post-realization posture. Consequently, the official line would be that we should not sit that way, that it’s an arrogant posture to take.

But that seems wrong to me, for a few reasons: For one, there are very good reasons to reverse our legs every time we sit. This posture can be hard on the knees, and also on the back — switching regularly brings more balance to the body, and also takes stress off the legs. But if we switch the legs without switching the hands, there’s an imbalance there as well. If, for example, you’re Sitting in Practice, naturally your left heel (which is on the right thigh) will be slightly lower than the right heel (which is higher up on the left thigh). If you’re resting your mudra on the heels, then the lowered right hand compensates for that difference — very elegant. But if you switch legs without switching hands, you’re putting the raised heel under the right hand, tilting the mudra (and by extension your arms, and by extension the body). They’re a set.

The other reason is simply this: in a practice based on the working assumption that everyone is already fully buddha, and that zazen is the activity of a buddha, and that only buddhas can sit in zazen, it’s absurd to make some distinction between how “we” should sit and how a “buddha” should sit. It’s silly.

A final benefit is that for someone who wasn’t taught this way, switching the hands (a lot of people switch the legs — that part isn’t radical) makes zazen less comfortable and familiar. And sometimes, that’s good.

For the record, I know of exactly one teacher who recommends that people try Sitting in Verification once, as a kind of bold experiment and statement of buddhahood. But I don’t know anyone besides me who says it should always be on the menu.

I hope that’s helpful. Take care.

Gassho,

-koun

If I could empty my thoughts in a Zazen bowl, and stir them up, and they ended up tasting like this lovely text that you have written, I would bow and smila and bow again. And I am doing just that.

I have been thinking a great deal about Dogen, and then reading Red Pine’s rather novel translation of the Heart Sutra, and then sitting and considering what it means that I am doing those things. So, I suppose I’m a little bit Zen-drunk. Is our way of talking about Zazen just a little bit rusty? Sometimes, it is. (And I really enjoy the rust in Dogen’s writing). Dogen is a fine place to start. Ass-on-cushion is a fine place to start. Your instructions are a fine place to start.

I think what you wrote is not out of touch with what I hear about our Zen ancestors, those compassionate ripples that I hear from rocks tossed in ponds a long time-being ago.

Deep Gassho,

Genku

thank you for taking the time to explain the answer to this small question of mine, I guess I’m so afraid I’ll “miss something” I need. I find your posts and comments very instructive. take good care.

gassho,

Robert

[…] of recent blog posts by Americans who have ended up practicing for a long time in Japan. One by Koun Franz, and another by Jundo […]

Hi, Koun,

I so appreciate that you write down your thoughts concerning practice. I too feel that the ability to communicate the heart of the practice in words is a necessity in our circumstance, and I undertake to communicate first and foremost to myself. A child of the age of science in the West, and yet there is science at the heart of Gautama’s teaching and Yuanwu’s, I can feel it.

I would like to respectfully suggest that the strongest communication is positive and substantive.

I’ve been writing a manual of zazen for ten years now, on my own site, primarily to benefit myself. From the first, I have aimed to gain an appreciation for what Gautama described as his way of life before enlightenment, the best of ways, and the way of life of the Tathagatha, in light of the teachings of Yuanwu and Dogen and the Zen tradition.

I had a funny experience a couple of weeks ago, and so here is my latest “note to self” concerning zazen:

http://www.zenmudra.com/zenmudra-best-of-ways.html

sincerely,

Mark Foote

Mark, thank you. I’ve read some of your work before and always found it fascinating. To anyone listening: take a look.

Thanks very much for your kind words, Koun. I neglected to say that I agree with you entirely concerning sitting left leg on top and right leg on top; I got it from my Judo teacher in high school, who insisted we practice the throws left side and right side, both.

“Take seven long breaths. As you inhale, fill the body with a wind that loops through your feet and across your thumbs. As you exhale, do so slowly, continuing until your breath has touched the far corners of the world. Exhale until nothing remains.”

I just added this quote to my own blog, although I didn’t offer any explanation:

“When old Master Chien-hou taught people, he always quoted the Classics: ‘The feet, legs, and waist must act together simultaneously.’ He also quoted the line: ‘It is rooted in the feet, released through the legs, controlled by the waist, and manifested through the fingers’…”

(“Cheng Tzu’s Thirteen Treatises on Ta’i Chi Chuan”, Cheng Man Ch’ing, trans. Benjamin Pang Jeng Lo and Martin Inn, pg 105)

As to touching the far corners of the world, we have this practice, mentioned by Gautama:

“[One] dwells, having suffused the first quarter [of the world] with friendliness, likewise the second, likewise the third, likewise the fourth; just so above, below, across; [one] dwells having suffused the whole world everywhere, in every way, with a mind of friendliness that is far-reaching, wide-spread, immeasurable, without enmity, without malevolence. [One] dwells having suffused the first quarter with a mind of compassion… sympathetic joy… equanimity that is far-reaching, wide-spread, immeasurable, without enmity, without malevolence.”

(MN I 38, Pali Text Society volume I pg 48)

That Gautama’s way of life involved such as the above in inhalation and exhalation seems clear to me; what my way of life must be, I am open, or as a friend of mine saw fit to tattoo on his forearm, “I am here”.

[…] mention this idea when I first give instructions in zazen, but just to plant a seed. I don’t expect anyone to sit in that way on the first day or the first […]